Damp, chilly, end-of November/early-December days call for the kind of coziness that can only be achieved by curling up in a warm place with a hot drink and a good book. In my case, the most recent book was Stephanie Barron’s The White Garden: A Novel of Virginia Woolf.

Damp, chilly, end-of November/early-December days call for the kind of coziness that can only be achieved by curling up in a warm place with a hot drink and a good book. In my case, the most recent book was Stephanie Barron’s The White Garden: A Novel of Virginia Woolf.

On the surface, the mystery’s title is misleading. Any serious gardener knows that the “White Garden” belonged not to early twentieth century author, Virginia Woolf, but to her good friend and sometime paramour, Vita Sackville-West—1892-1962. The two writers led intertwined lives, along with their fellow members of the literary, artistic and aggressively bohemian Bloomsbury group. Without giving away critical plot details, it is enough to say that Barron assigns Woolf a pivotal role in the creation of the now-fabled White Garden at Sackville-West’s estate, Sissinghurst.

Vita pursued and achieved serious literary stature throughout her life, but these days she is best known for the garden she made with her husband, diplomat Harold Nicolson. Her adventures in horticulture, literature and travel also resulted in singularly beautiful garden writing, most frequently published in England’s Observer newspaper from 1946-1961. Garden writers still quote Vita all the time, because in addition to being an evocative prose stylist and a superb gardener, she was eminently quotable.

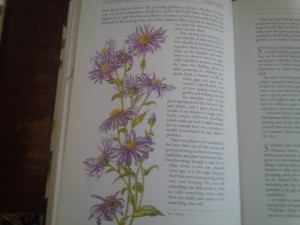

I frequently turn to Vita for inspiration. One of the best volumes in my gardener’s library is a collection of her Observer columns, V. Sackville-West: The Illustrated Garden Book. The writing is a treat all by itself, but the anthology has a double layer of icing on the cake—a forward by Oxford don and gardening authority Robin Lane Fox and gorgeous watercolor illustrations by Freda Titford. I have the hard cover edition, first published in 1986. It is still available from used book sellers, along with a subsequent paperback version.

I frequently turn to Vita for inspiration. One of the best volumes in my gardener’s library is a collection of her Observer columns, V. Sackville-West: The Illustrated Garden Book. The writing is a treat all by itself, but the anthology has a double layer of icing on the cake—a forward by Oxford don and gardening authority Robin Lane Fox and gorgeous watercolor illustrations by Freda Titford. I have the hard cover edition, first published in 1986. It is still available from used book sellers, along with a subsequent paperback version.

In November and December, Vita undertakes the obligatory writing about bark, berries and garden structure, but she dreams of flowers. She “rounds off November” by describing a double handful of plants that make excellent flowering hedges, dwelling on the glories of roses, barberries, flowering quince and Japanese keria. While singing the praises of ornamental hedges, she also acknowledges life’s realities, describing the thorny hedging plants that are most suitable “for the exclusion of cattle and small boys.’

When December arrives, the writer laments that it is hard to find even a few garden flowers to brighten up the indoor scene. Compensation at Sissinghurst comes in the form of winter-flowering cherry or Prunus subhirtella ‘Autumnalis’, which, at least for Sackville-West, produces branches for indoor forcing from November to March. She mentions the pink form of this small tree, but saves her highest praise of for winter-flowering cherries with pure white blossoms. Vita values the cherry’s resilience: “Even if frost catches some of the buds, it seems able, valiant little thing that it is, to create a fresh supply.”

One December column takes wing on the smallest puff of airy prose–“It is amusing to make one-color gardens.” No one, probably least of all Vita, knew it at the time, but those words would turn out to be significant in the history of the Sissinghurst landscape and horticulture in general. The one color was, of course, white, which the author extended to include silvery and grayish white foliage plants like aromatic wormwood or Artemisia, and santolina, sometimes known as lavender cotton. Those colors came together at Sissinghurst in the area now known worldwide as the “White Garden”. It has been discussed and imitated ever since.

Vita envisioned an array of classic spring and summer flowers, including “dozens of Regale lilies” or Lilium regale, shooting up amid the foliage plants. These showy, fragrant lilies, which are still best-sellers, soar to five feet tall, with each mature stalk bearing up to 25 golden-throated, white trumpets. The petal reverses show purple stripes. The garden Vita projected in the column would also be home to all kinds of romantic pale blooms, including “white pansies, and white paeonies, and white irises with their grey leaves…” It was meant to be resplendent all the time, but especially luminous at twilight.

The last paragraph of Vita’s column on the White Garden is all anyone needs to set a scene and find inspiration, even on the most unpromising winter day:

“…I cannot help hoping that the great ghostly barn-owl will sweep silently across a pale garden, next summer, in the twilight, the pale garden that I am now planting, under the first flakes of snow.”