The selling of souls is serious business; just ask the poets and playwrights who have explored that theme over the centuries. Gardeners generally have little time for such existential considerations, because they are busy weeding, watering and doing other garden chores. But every once in awhile, a plant comes along that is so alluring, it might inspire that kind of thinking. For me that plant is lupine.

The selling of souls is serious business; just ask the poets and playwrights who have explored that theme over the centuries. Gardeners generally have little time for such existential considerations, because they are busy weeding, watering and doing other garden chores. But every once in awhile, a plant comes along that is so alluring, it might inspire that kind of thinking. For me that plant is lupine.

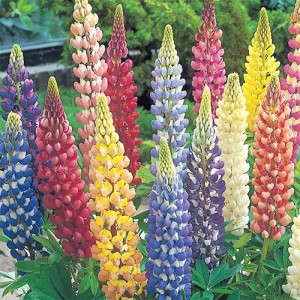

A healthy stand of lupines, or Lupinus hybridus, in the early summer is a glorious thing. The stalks are tall–up to four feet–and topped by erect, conical flower spikes made up of scores of fragrant, pea-like blooms in shades of blue, purple, pink, red, white or yellow. If you turned the spikes upside down, they would bear more than a passing resemblance to wisteria, which is no coincidence. Wisteria and lupine are closely related members of the bean or Fabiaceae family.

It is hard to beat the beauty of the flowers, but lupine foliage is attractive in its own right. Appearing alternately on the stalks, the leaves are palmate or hand-shaped, and divided into anywhere from five to 12 leaflets. Once the flowers are finished, the plants produce silky seed pods that eventually explode, dispersing seed over a wide area.

So why do I not just cover my garden beds with a glorious array of lupines? Because I live in a climate where the soil is sticky clay and the summers tend to be hot and humid. Lupines abhor those conditions. At best they will perform half-heartedly and at worst they will refuse to perform at all.

You can amend soil, but climate is a deal breaker. Lupines do nicely in England’s cool summer climate. They also thrive in New England, Canada and the Pacific Northwest. They even work well as winter annuals in parts of the South.

There is only one problem. I don’t live in any of those places.

That does not mean, however, that some local garden centers won’t occasionally carry lupines, or that I won’t buy them. Hope springs eternal, even if that hope is only wishful thinking facilitated by a credit card. I have planted and tended those wishfully-purchased lupines, amending the soil and giving them the consistent moisture they require. I have rewarded them with choice garden sites, where there is ample sun and good air circulation. All of that slavish devotion has netted me exactly one lupine success in many years of gardening. That happened in a year when, for some reason, my area experienced an elongated cool spring that morphed into an uncommonly moderate summer. The lupines, which went into the ground in the spring, flowered beautifully. I was ecstatic.

The following year, the climate reverted to its normal state and the lupines responded with a few half-hearted leaves and no flowers. It was depressing.

To deal with that depression, I did lots of research, hoping that somewhere in my many horticultural reference volumes or in the far reaches of cyberspace, I might find a lupine variety that was resistant to heat and humidity. Along the way, I reveled in the romantic story of George Russell—1857-1951–an amateur English hybridizer who was responsible for the development of the modern lupine. Russell’s successors have done much to revive the Russell strains, but as yet, no one has perfected a heat and humidity resistant variety.

Of course I could cheat and buy mature lupine plants in bud and use them as annuals, but that is an expensive way to satisfy the urge. Until someone comes up with a lupine that is better acclimated to my climate, I’ll have to content myself with its relative, hybrid baptisia or false indigo, which also bears pea-like flowers. The blooms are not as tightly clustered on the stalks and the plants are wider, but the colors—blues, blue-purples, yellows and white—are similar to those of lupines. Some varieties also boast striking black seed pods that are decorative at the end of the growing season.

Baptisia is very fashionable right now, and easy to come by. Happy clumps grow larger as the years go by, so I will never run out of baptisia.

Still, if I ever run into a lupine that likes New Jersey, I will root out the baptisia and install the lupine. Hope, unlike lupines, springs eternal.