The rose is the Mona Lisa of the plant world. For millennia, humans have coveted them, grown them, celebrated them in every art form and sought out new forms and varieties. Some of us, especially those who have to do hand-to-hand combat with blackspot and other rose diseases, have occasionally cursed them. But the fascination remains.

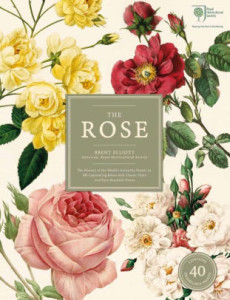

Now there is yet another book that seeks to tell their story. The Rose: The History of the World’s Favourite Flower in 40 Captivating Roses With Classic Texts and Beautiful Rare Prints is a cumbersome title for an excellent book. Written by Brent Elliott, rosarian and historian of England’s Royal Horticultural Society, The Rose combines history, botany, horticulture and art to shed light on the rose family tree, as well as the ebb and flow of rose fashion. Though the big holiday gift giving season has passed, the book would make a nice birthday or anniversary present for a rose loving friend. It might make an even better gift for yourself.

The handsome paperback volume comes in an eye-catching slipcase, which also holds the “beautiful rare prints” advertised in a title. These are suitable for framing and would make a nice rose gallery.

Art is one of the glories of The Rose. The forty chapters are lavishly illustrated with paintings, woodcuts, prints, drawings, catalog art and even advertising material from the Royal Horticultural Society’s Lindley Library. Many of the great botanical artists are represented, including the most famous of all–Pierre Joseph Redoute, celebrated for his portraits of the Empress Josephine’s roses and other flowers.

Elliott takes us back to the earliest descriptions and representations of roses, quoting or citing writers including the Greek botanist, Theophrastus, in the third century B.C. and the celebrated Roman naturalist, Pliny, in the first century A.D. The author has the unenviable job of trying to figure out which roses various writers were talking about, in the full knowledge that many rose descriptions—from ancient times until the present—are more poetic than botanically accurate.

The author also seeks to debunk popular rose myths. The beautiful and fragrant Damask rose, for example, which is still available from specialty growers, was long thought to have arrived in Europe with returning Crusaders in the eleventh or twelfth centuries. It is a romantic myth, says Elliott, but not one grounded in fact. Damask roses are not found growing wild anywhere in the Middle East and are more likely the result of spontaneous cross-breeding of European roses.

The book introduces the reader to the species roses found in Europe and America, tracing chains of horticultural references to pin down their origins. I especially like the chapter heading for the section on American natives—“Roses of America: Confusions from the New World.”

Elliott takes on European white roses, European red roses, and—clearly a favorite—European striped roses. He grapples with the myth of the most celebrated striped bloom, Rosa gallica versicolor, often known as “Rosa Mundi”. Allegedly this rose, which I grow in my home garden, got its common name from Rosamund Clifford, mistress of the English king, Henry II. Not only was the rose supposedly named for “Fair Rosamund”, but the lady in question was purportedly murdered by Henry’s strong-willed and fabled wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Despite the best efforts of poets, writers and movie makers, neither story is true. Rosa Mundi appeared in the seventeenth century, long after Rosamund Clifford’s death in the twelfth.

Though The Rose has a pronounced European orientation, the author does give full credit to one of the great developments in rose history—the eighteenth century arrival of Chinese roses in Europe. This development expanded the range of rose colors and forms and brought the invaluable reblooming trait to the rose world. The Chinese “stud roses” made possible all the types that came after, from Portlands to Noisettes to Hybrid Perpetuals; right down to modern hybrid teas, which did not appear on the scene until the introduction of ‘La France’ in 1868.

Elliott includes some interesting sections on the language of flowers and the development of rose gardens. I especially love the pictures of all the fascinating forms that Victorians used to train climbing and rambling types.

At its heart, The Rose is a book about the relationship between human beings and roses. We are fortunate that despite the fact that humans have collected roses in the wild, engaged in centuries of selective breeding, forced them to climb walls, tortured them into tree form and generally tried to bend the entire genus to our will, roses persist. They don’t really need us, but Elliott presents ample evidence to suggest that we need them.