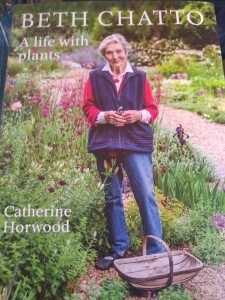

The latter half of the twentieth century produced a bumper crop of great gardeners, garden designers and garden personalities. I have been inspired by many of them, especially British born Beth Chatto, 1923-2018, who shone brightly in that horticultural pantheon. Now, an authorized biography, Beth Chatto: A Life With Plants, presents a fond, but unvarnished look at Chatto’s life and work.

The latter half of the twentieth century produced a bumper crop of great gardeners, garden designers and garden personalities. I have been inspired by many of them, especially British born Beth Chatto, 1923-2018, who shone brightly in that horticultural pantheon. Now, an authorized biography, Beth Chatto: A Life With Plants, presents a fond, but unvarnished look at Chatto’s life and work.

Unlike other garden luminaries like Vita Sackville West, Chatto did not start her life as an aristocrat, surrounded from birth by fabled gardens. She was the daughter of a village constable and his wife who kept a typical English cottage garden and prided themselves on growing their own vegetables. The seeds of Beth Chatto’s career were sown in that home garden and fertilized by the precocious child’s belief that she was “driven or had the energy to discover a wider world.”

Chatto trained to be a teacher and had just embarked on that career when she married Andrew Chatto, a fruit farmer who came from a wealthy publishing family. Despite a fourteen year age difference, the couple’s shared interests in botany and horticulture brought and kept them together.

Beth Chatto gave up teaching with the birth of first child and turned her prodigious energies to gardening and flower arranging, entering shows and winning ever-more prestigious prizes. She made a name for herself by using garden plants, flowers, and even vegetable materials rather than florists’ specimens. An award-winning 1957 arrangement, for example, featured “onion heads, artichoke thistles, ballota, giant eryngiums.” These early arrangements echoed the naturalistic compositions of society florist Constance Spry, who was famous for making artistic use of garden flowers, roadside weeds and other non-traditional materials.

Eventually Chatto decided to open a small nursery on part of the farm property. Her nursery offerings and displays were created with the same sensibility as her arrangements, going beyond colorful flowers into thoughtful groupings of plants with complementary textures, forms and, especially, cultural needs. The nursery caught on, and to boost sales, she began issuing printed plant lists for mail order customers. These efforts, plus Chatto’s enormous talent for finding and introducing new plant specimens, connecting with like-minded plantspeople, and inspiring others through her writings and presentations, led to an invitation in 1976 to exhibit a nursery display at the Royal Horticultural Society’s Chelsea Flower Show.

At the time, other plant vendors arranged their offerings “in serried ranks of visible pots at various levels”. Within the confines of a relatively small stand, Chatto created a garden-like arrangement with plants grouped in a naturalistic way according to their preferred conditions—dry/ sunny, or cool/shady. The display was a hit with attendees, as well as judges, who awarded her one of the Silver Gilt—second place—medals. She was disappointed not to win a Gold Medal, but returned in 1977 and went home with her first gold.

Chelsea success brought her fame, along with speaking and book offers. Her first book, The Dry Garden, was published in 1978. This was followed by more books, including; The Damp Garden; Plant Portraits; Beth Chatto’s Garden Notebook; The Green Tapestry; Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden; Beth Chatto’s Shade Garden; and, with her friend and fellow plantsman, Christopher Lloyd, Dear Friend and Gardener. All are still available and should be required reading for committed gardeners.

By the time of Beth Chatto’s death in 2018, she was known worldwide in horticultural circles. Her nursery, expanded far beyond its original confines and featuring numerous specialty display gardens, is still a “must see” for garden tourists visiting England.

What made Beth Chatto so special? She combined an artist’s feeling for color, texture, composition and balance with an incredible knowledge of plants. She was one of the leading practitioners of the “right plant, right place” philosophy, maintaining that close attention to plants’ cultural needs and preferred habitats would lead to successful gardens and landscapes. Her gravel garden, for example, composed mostly of drought-resistant Mediterranean plants and mulched with gravel, has almost never required supplemental water.

Though she used flowers to great effect in her arrangements and gardens, she knew that successful gardens had to encompass much more, including foliage, fruits and seedheads. She “painted” with plants, creating combinations that were both beautiful and sustainable. Perhaps most important of all, she proved that purposeful environmentalism is not only compatible with inspiring gardens, but essential to sustaining them. Her philosophy is as vital today as it was the day she won her first Gold Medal.