Several years ago, I read and wrote about Meryl Gordon’s literate and comprehensive biography of Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon, garden designer, tastemaker and socialite, who died in 2007. Bunny Mellon: The Life of an American Style Legend took Bunny through a long and eventful life that included the accomplishment for which she is most often remembered, the Kennedy-era design of the White House Rose Garden.

Several years ago, I read and wrote about Meryl Gordon’s literate and comprehensive biography of Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon, garden designer, tastemaker and socialite, who died in 2007. Bunny Mellon: The Life of an American Style Legend took Bunny through a long and eventful life that included the accomplishment for which she is most often remembered, the Kennedy-era design of the White House Rose Garden.

Bunny Mellon’s life was full of highs and lows—lifelong wealth, punctuated by two marriages, influential friendships, and twin passions for style and perfection. Gardening was one of the constants in that life, and the passion that most interested me. I will never have a Givenchy gardening smock like Bunny’s, but I will always be a gardener. After reading the biography, I longed to know more about the Mellon gardens and garden philosophy.

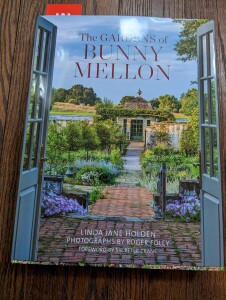

A Christmas elf granted my wish by leaving The Gardens of Bunny Mellon by Linda Jane Holden under the tree. Large, lavishly illustrated, and published in 2018, the book was astronomically priced when it came out. At the time, I refused to plunk down such an enormous sum, even to slake my thirst for more information about Bunny Mellon’s horticultural achievements. I figured the price would eventually come down, and it did. My daughter was able to pick it up online for a small fraction of the original cost.

Bunny had gardens of her own, at her primary home in Virginia, and vacation spots in Cape Cod, Nantucket and Antigua. After her initial foray into design, she also worked on gardens elsewhere, including at the Kennedy Library in Boston, and the late president’s gravesite at Arlington National Cemetery. Later in life, she collaborated with her favored designer, Hubert de Givenchy, on gardens at his estate, the Chateau du Jonchet, outside of Paris. When the Potage du Roi, or king’s kitchen garden, at Versailles needed restoration, Givenchy once again collaborated with Bunny.

She was an autodidact, reading and acquiring gardening books and manuals, including historic works, from a young age. In her travels, she also had access to some of the great gardens of the world. There is no doubt that her enormous wealth and personal connections made those important design assignments, like the White House Rose Garden, possible, but Bunny’s innate good taste and insatiable desire to increase her horticultural knowledge gave her work lasting value.

As I paged through the beautiful photographs by Roger Foley and read the accompanying text, I was struck by two ideas that were “north stars” for Bunny Mellon. The first was “nothing should be noticed,” meaning, I think, that a landscape should be a harmonious whole, springing from a single artistic concept, without jarring or uncharacteristic elements. The second was a more practical and dynamic principle, which required the gardener to look at an entire landscape, or a portion of it, and make two lists, one of elements that worked for one reason or another, and the second of elements that did not work. The latter would be removed.

How do those ideas work in an ordinary home garden for individuals who have neither the Mellon wealth, nor the army of garden workers who were always at Bunny Mellon’s disposal? It depends on where you start. Sometimes, an individual acquires a property with existing plantings installed by the previous owner. If that person simply hired a run-of-the-mill landscape contractor to install plantings, the contractor probably put in shrubs and small trees that are relatively inexpensive and known to work well in the local area. This “concept” pleases realtors because it is neat, generically attractive, and follows Bunny’s dicta that nothing should be noticed. On the plus side, it allows a new homeowner to figure out what should be on the “keep” and “discard” lists, and remove those elements that don’t meet the individual’s aesthetic preferences.

If you luck into a property with an established garden, you can apply the same principals, but it pays to do a little prep work. Talking to the previous owner, if possible, will give you an idea of what that person had in mind in choosing plantings and arranging the landscape. If a landscape or garden designer had a hand in the effort, there may be plans to examine. Watchful waiting is also a good idea in the first year of experiencing an existing garden. It is hard to know how plantings work together until you have been through an entire growing season. Using pots of annuals to fill in gaps is a good way of beginning to make the garden your own while going through the watchful waiting period.

If you have owned and gardened on your property for a long time, you can probably skip to the list-making phase, and plan for removal of elements that don’t work, have outgrown their allotted spaces, or no longer match your overall garden concept. People evolve over time—or should—and gardens do too. It makes sense to use Bunny’s very practical approach to re-evaluating your home landscape.

I tend to garden rather instinctively with a magpie’s approach to acquiring plants. Still, I do have an overall concept that has gained sharper focus in the years since I acquired my current property. As we move towards the start of the new gardening season, I intend to use Bunny’s list-making approach to re-invigorate my garden.